Tina, a 52-year-old female, recently received the results of an x-ray of her knee. Three months ago, she started to have pain in the inner part of her knee that had progressively worsened and affected her ability to walk. Her primary care physician ordered an x-ray to investigate further. The imaging results revealed “medial compartment narrowing with the moderate presence of osteophytes.” Osteophytes is the medical term for “bone spurs”. While the x-ray was not able to provide any information of the status of her meniscus or articular cartilage, her primary care physician referred her to an orthopedic physician regardless. Tina is concerned that she will be advised to have a total knee replacement which she would like to avoid.

The pathophysiology of knee osteoarthritis, or how the knee adapts to injury or trauma, has a few common features. Joint narrowing, cartilage thinning, meniscal extrusion and the development of osteophytes, or bone spurs, are several of the features that are associated with an osteoarthritic knee. In this article we will be discussing osteophytes, their presence in a joint and whether they are indicative of disease or a prediction of disease.

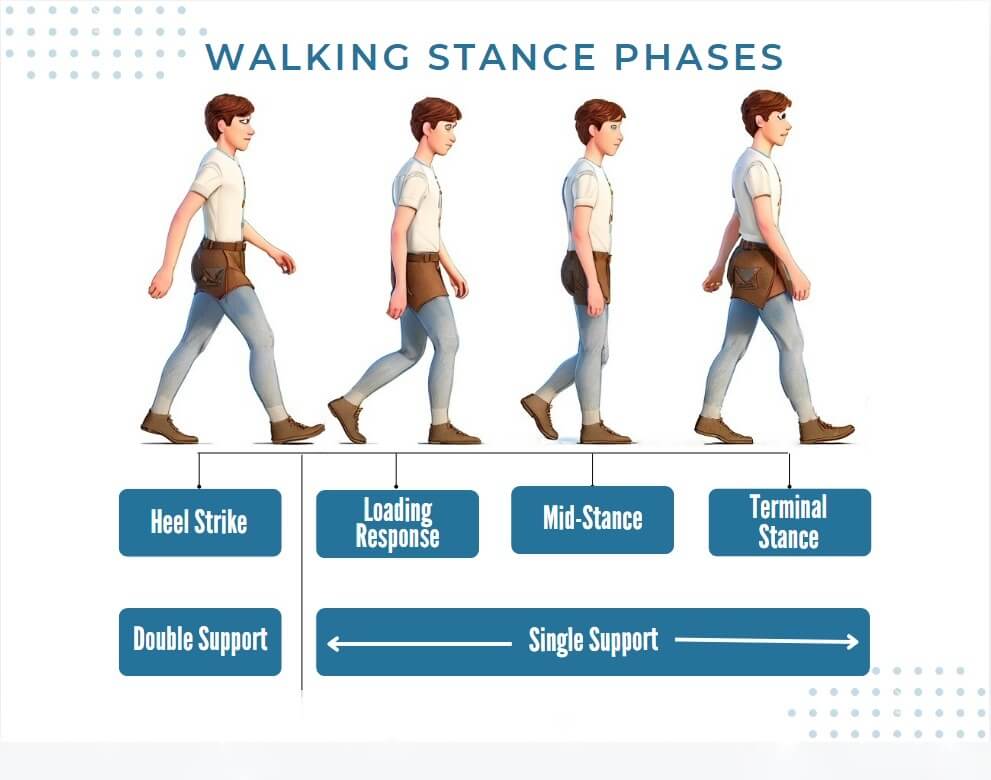

In the late 1890’s, after many years of performing joint surgeries, a German surgeon named Julius Wolff developed a theory appropriately known as Wolff’s Law. This law states that when there is repetitive load placed on a bone, it remodels itself. Of course, in the late 1800s Dr. Wolff had no understanding of the cellular processes involved in bone remodeling. Nevertheless, his observations were correct. There is a delicate cellular balancing act that occurs with bone formation, involving osteoblasts, osteoclasts and osteocytes as well as interplay from hormones which is beyond the scope of this discussion. Suffice it to say that when repetitive loads are placed on a joint there is a resultant symphony of events culminating in bone formation1. In a 2003 study, of 20 healthy women without knee osteoarthritis, researchers determined that there was greater lateral load, or load from the outside of the knee towards the inside of the knee during the mid and late phases of walking.2 Below is a diagram and list of the phases of walking (Fig 1) .

- Initial contact (heel strike)

- Loading response (foot flat)

- Mid-stance

- Terminal stance (heel off)

According to this study, the highlighted area has been shown to have the greatest lateral to medial, or outer knee to inner knee, load during walking, placing greater pressure on the inner side of the knee. As a result, there was greater bone formation in the medial tibial plateau in these women’s knees. This is consistent with Wolff’s law. Adduction moment of a knee, outer to inner load, is responsible for greater bone formation in the lower leg bone called the tibia.

While the bone remodels itself from repetitive loading cycles, the articular cartilage, or the cartilage that lines the ends of the bones, does not remodel itself to repetitive load. Cartilage thickness is the true determination of the health of a joint. Articular cartilage thinning may be a result of an old subchondral bone, or bone beneath the articular cartilage, injury or meniscus tear. When the fluid that bathes the joint, known as the synovial fluid, becomes chronically inflamed from a subchondral bone or meniscal injury, it damages the integrity of the articular cartilage. Ultimately, the formation of bone spurs is likely a forecast for the progression of knee osteoarthritis as the load is no longer evenly distributed due to injury. The combination of lateral to medial load that naturally occurs with walking combined with articular damage leads to a maladaptive development of medial bone spurs.

Tina was examined under ultrasound at our office and not only were there bone spurs present in the medial side of her knee, but she also had a narrow medial joint line, a visible tear in her extruded, or outpouched, meniscus and tenderness on the inside of her knee. Tina is an excellent candidate for adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells (AD-MSCs) combined with knee rehabilitation and strengthening therapy to avoid a total knee replacement. The AD-MSCs will significantly reduce her pain by neutralizing the synovial fluid in the joint and repair both the meniscal tear and articular cartilage. The osteophytes will persist but without the associated pain.

Dr. Stacey Guggino, ND, LAc, graduated from the National College of Natural Medicine in Portland, Oregon with a Doctorate in Naturopathy and a master’s degree in Oriental Medicine. For the past 12 years, she has specialized in treating pain and sports injuries with acupuncture and prolotherapy. Dr. Guggino has also studied and practiced aesthetic medicine for 11 years.

Sources

- ↑ Teichtahl AJ, Wluka AE, Wijethilake P, Wang Y, Ghasem-Zadeh A, Cicuttini FM. Wolff’s law in action: a mechanism for early knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015 Sep 1;17(1):207.

- ↑ B. D. Jackson, A. J. Teichtahl, M. E. Morris, A. E. Wluka, S. R. Davis, F. M. Cicuttini, “The effect of the knee adduction moment on tibial cartilage volume and bone size in healthy women”. Rheumatology, Volume 43, Issue 3, March 2004, Pages 311–314