Mary is a 66-year-old female who is postmenopausal, with elevated stress, osteopenia, low mood, and increased fatigue. She recently saw her general practitioner who started her on a low dose antidepressant, recommended calcium and vitamin D supplementation and encouraged counseling. After six weeks of the anti-depressant, Mary continues to have a low mood, flat affect, poor motivation and fatigue. While the counseling is helpful, her management of stress continues to be a strain. Mary is desperate to feel better and have certainty about her health. What other approach to care and treatment would be suitable for Mary?

At Oregon Regenerative Medicine, we consistently look deeper for the cause of our patients’ symptoms. Our functional medicine training is focused on evaluating the different body systems, how these systems interact with one another and ultimately result in a patient’s symptoms. Rather than solely treating symptoms, eliminating the root cause of those symptoms is our goal.

Upon further evaluation, we find that Mary has dealt with lifelong depression. She says that it worsened going into menopause and that she also experiences poor sleep, breast tenderness and her gastrointestinal health has also been abnormal, experiencing gas, bloating and alternating diarrhea and constipation.

As a clinician, I am most curious about Mary’s stress. Mary needs to be evaluated for what is going on in her HPA axis, or hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. The HPA axis is responsible for dealing with day-to-day stressors. It adjusts our immune system, metabolism and autonomic nervous system to deal with stress. When there is psychological or physical stress our adrenal cortex releases cortisol. Cortisol is the “fight-flight” hormone that generates glucose, or fuel, for the muscles and the brain. This enables the muscles and brain to operate and direct our body away from a stressor. But the problem is that cortisol does this by tapping into protein and fat storage areas of the body and turns them into glucose. That’s called catabolism, and can lead to insulin resistance, muscle loss and bone loss.

DHEA: The adrenal’s anti-stress bank account

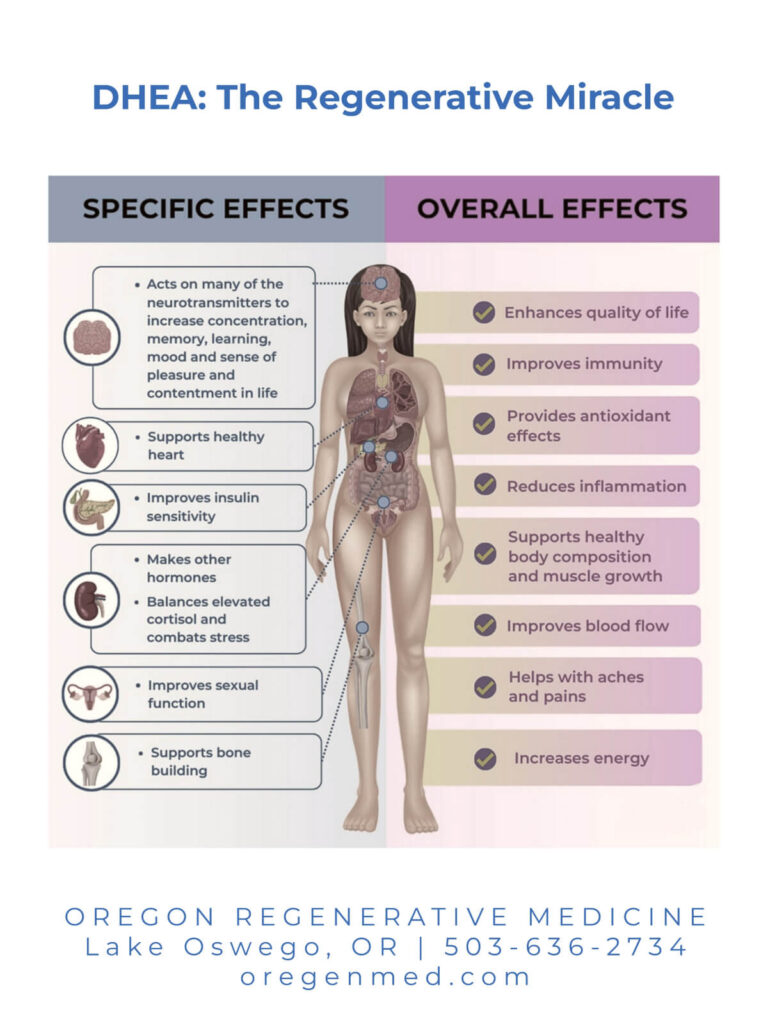

DHEA is also released when there is a stressor. DHEA, or dehydroepiandrosterone, is anabolic in nature. In other words it is used to build tissue. Produced in high amounts when we are young, DHEA production peaks in our mid-twenties and falls as we age. It promotes muscle and bone growth by increasing both testosterone and estrogen. It also promotes cognition and motor skills by increasing something known as nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor1. Additionally, DHEA dampens the inflammatory cytokines, or chemical messengers which accelerates wound injury healing2. Its anabolic nature is why this hormone has a reputation for being “regenerative” or anti-aging.

In essence, when there is stress, both cortisol and DHEA are produced and the DHEA keeps the catabolic nature of cortisol in check. However, as we age and are chronically stressed and depressed, the production of DHEA is reduced. Research has shown that by the age of 70-80, we have 10-20% less of the DHEA found in young people3. This causes an imbalance in the ratio between DHEA and cortisol leading to some potential pro-aging ailments4:

- bone and muscle loss

- increased body inflammation

- frequent bowel movements

- loose stools

- long bouts of severe abdominal pain

- less energy and lower mood

In conclusion, Mary’s journey towards improved health and well-being is a complicated puzzle that requires a holistic approach. At Oregon Regenerative Medicine, we are dedicated to understanding the root causes of our patients’ symptoms rather than merely addressing surface-level issues. In Mary’s case, her lifelong battle with depression, compounded by the challenges of menopause and persistent stress, has led to an imbalance in her DHEA and cortisol levels. The intricate interplay between these hormones influences various aspects of her health, from mood and energy to bone and muscle maintenance.

Recognizing the importance of DHEA in the body’s regenerative processes, we are committed to conducting a thorough assessment of Mary’s hormone levels, particularly cortisol and DHEA, throughout the day. By identifying these imbalances, we can tailor our approach to supplementing her appropriately and helping her regain equilibrium.

It’s essential to keep in mind that maintaining proper thyroid health and monitoring sex hormone levels are also crucial aspects of Mary’s care. In this complex journey toward wellness, having a trusted physician’s guidance and support is paramount. Mary’s case serves as a testament to the sophisticated and interconnected nature of our health. We are dedicated to helping her, and others like her, achieve a healthier and happier life through personalized, regenerative care.

Here is a graphic showing some of the many roles that DHEA plays in our bodies:

Dr. Stacey Guggino, ND, LAc graduated from the National College of Natural Medicine in Portland, Oregon with a Doctorate in Naturopathy and a Master’s degree in Oriental Medicine. For the past 12 years, she has specialized in treating pain and sports injuries with acupuncture and prolotherapy. Dr. Guggino has also studied and practiced aesthetic medicine for 11 years.

Sources

- “Dehydroepiandrosterone: a potential therapeutic agent in the treatment and rehabilitation of the traumatically injured patient”. Conor Bentley et al. Burns & Trauma (2019) 7:26

- “DHEA-S production capacity in relation to perceived prolonged stress”. Anna-Karin Lennartsson et al.The International Journal on the Biology of Stress. Pages 105-112:17 Jan 2022

- “A Review of Age-Related Dehydroepiandrosterone Decline and Its Association with Well-Known Geriatric Syndromes: Is Treatment Beneficial?”.Rejuvenation Res. 2013 Aug; 16(4): 285–294.

- “Effect of prolonged stress on the adrenal hormones of individuals with irritable bowel syndrome”. Nagisa Sugaya et al. Biopsychosoc Med. 2015; 9: 4.